PREDICTIVE ECOLOGY IN A CHANGING WORLD.

Mouquet N. , Lagadeuc, Y., Devictor, V., Doyen, L., Duputie, A., Eveillard, D., Faure, D., Garnier, E., Gimenez, O., Huneman, P., Jabot, F., Jarne, P., Joly, D., Julliard, R., Kefi, S., Kergoat, G.J., Lavorel, S., Le Gall, L., Meslin, L., Morand, S., Morin, X., Morlon, H., Pinay, G., Pradel, R., Schurr, F.M., Thuiller, W. and Loreau, M. (2015).

Journal of Applied Ecology, 52, 1293-1310, doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12482

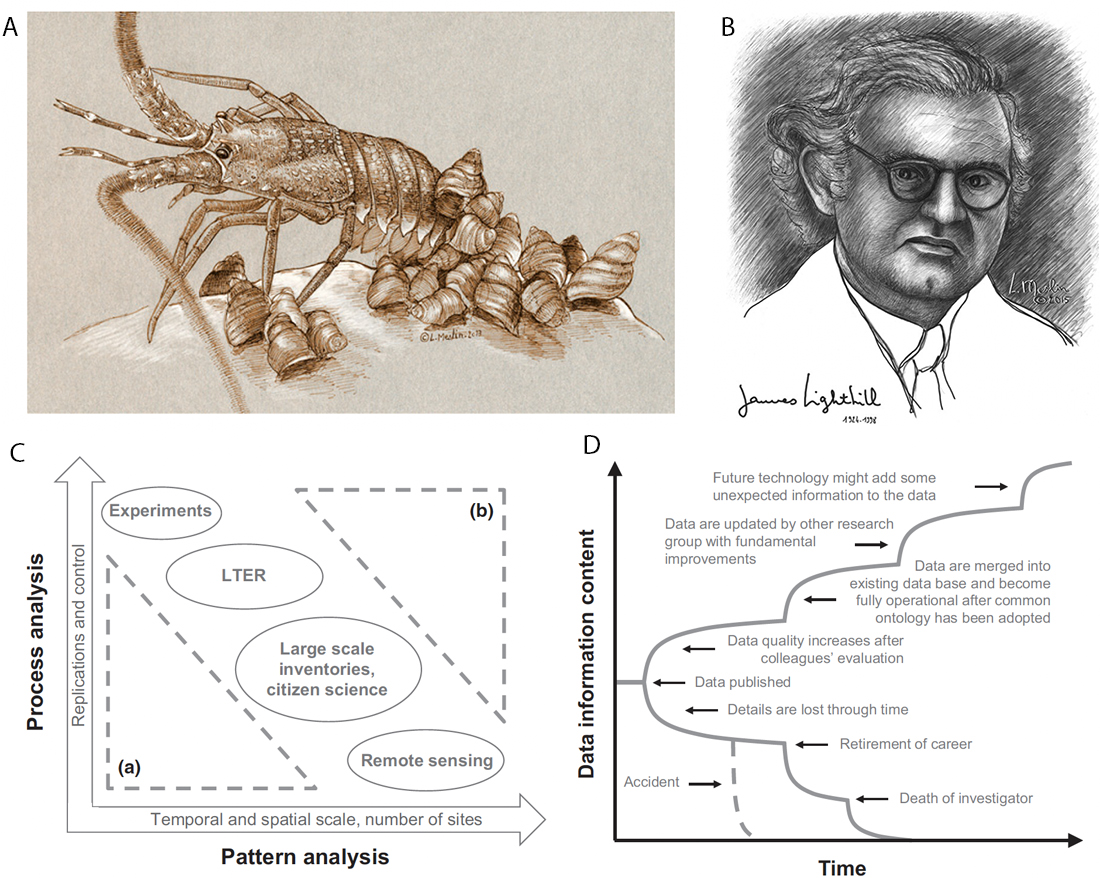

Key message : In a rapidly changing world, ecology has the potential to move from empirical and conceptual stages to application and management issues. It is now possible to make large-scale predictions up to continental or global scales, ranging from the future distribution of biological diversity to changes in ecosystem functioning and services. With these recent developments, ecology has a historical opportunity to become a major actor in the development of a sustainable human society. With this opportunity, however, also comes an important responsibility in developing appropriate predictive models, correctly interpreting their outcomes and communicating their limitations. Scientific ecology has a historical opportunity to become a major actor in the development of a sustainable human society. With this opportunity, however, also comes an important responsibility in developing appropriate predictive models, correctly interpreting their outcomes and communicating their limitations. Here, we use the context provided by the current surge of ecological predictions on the future of biodiversity to clarify what prediction means, and to pinpoint the challenges that should be addressed in order to improve predictive ecological models and the way they are understood and used. Ecologists face several challenges to ensure the healthy development of an operational predictive ecological science: (i) clarity on the distinction between explanatory and anticipatory predictions; (ii) developing new theories at the interface between explanatory and anticipatory predictions; (iii) open data to test and validate predictions; (iv) making predictions operational; and (v) developing a genuine ethics of prediction.